It seems like one of the hardest things to do – including other projects’ assets in your game.

We’ve covered why you’d want to include external assets. But an even bigger question is how. How does one navigate the technical, aesthetic, and IP challenges?

Well – how long is a piece of metaversal string?

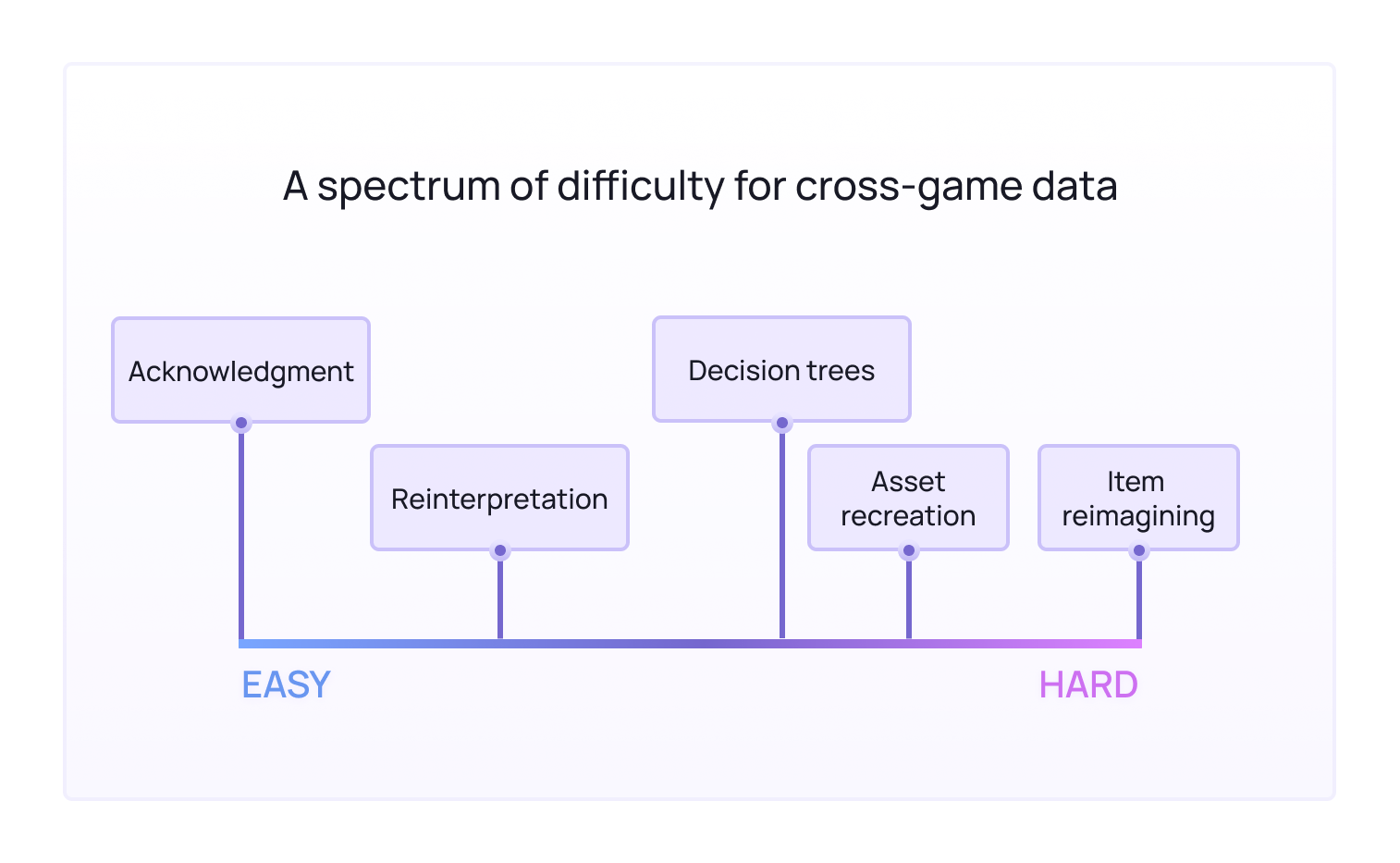

This is a process you can adapt to your needs. Implementations range from effortless to excruciating, with the latter reserved for fully recreated & reimagined 3D assets, matching the new world’s aesthetic, and its attributes scaled to slot into its new combat system & economy.

It’s that latter scenario that most people think about when they think of cross-game items, and that’s why many have labeled it impossible. But it doesn’t have to be that hard.

We’ll go through these different levels and talk about which situations they’ll be most useful in. But first, a disclaimer: these are by no means the only way cross-game items can be implemented. This is an unexplored frontier. What follows is a list of the most obvious low-hanging fruit that’ll perhaps one day be considered quaint and prototypical.

Rather than being a monumental effort, there are different solutions that scale according to what kind of interoperability you want.

The leftmost side of this scale represents the least labor. This is literally just looking for a particular token or family of tokens - or perhaps any token from a particular game or other project - and seeing it.

Not much is done beyond that. You can choose to offer a reward just for that NFT existing, and that reward can be whatever is easiest or best to conjure – in-game gold, a crafting essence, or just a hearty “attaboy.”

Funnily enough, a lot of stuff deemed “too hard” will end up here. The medieval sword NFT that doesn’t fit in a sci-fi game without a significant rework might be relegated to the “recognition” category. Check the wallet, see the token, grant some kind of resource or crafting essence, and call it a day.

Another option is metaversal assets unlocking game-bound experiences. A special key from another universe unlocks a door here, an achievement triggers an event there, a prior moral decision uncovers an easter egg, etc.

There are one-person teams using Enjin tools to leverage the power of an item marketplace, who don't have large teams but have the freedom to experiment with NFT metadata. As larger developers dip their toes, these lightweight devs will test how attributes scale in a new world and find ways to acknowledge the asset’s deeds in a previous life, in a previous universe.

Unrecognized attributes can be ignored, or translated into whatever the developer wants. The player essentially wanders into your world with a bag full of oddities, and you are both broker and pawn shop operator.

“+10 Strength?” you say, rubbing your chin. “Our universe has no Strength attribute, but we do have Resilience. How about we give you a scaled amount of Resilience?”

Throwing users some gold, or a trophy, after a wallet check is the easiest implementation possible. It gets harder when you start talking about actual dev-hours manipulating assets...

At the other extreme end of the spectrum, it gets even harder than the worst-case scenario that most people think of. But even here, it’s as hard as you make it.

Large teams may choose to make full 3D models that represent a player’s winnings in other games. This is a lot of effort for each item, but it could be worth it for the most memorable and storied items.

Before World of Warcraft had a million expansions, one of the hardest weapons to get in the game was Sulfuras, Hand of Ragnaros. It required repeated runs with an entire guild just to have a chance at scoring the materials.

That’s the type of item it’d be a no-brainer to recreate, importing all of its sentimental value and potentially rewarding the entire guild.

Adjacent to outright recreation (and arguably harder) is tasking your 3D artists to concoct a clever alchemical blend of the original item with your world’s aesthetic, making sure it really “lives” in your world.

As we alluded to before, there’s also a systems design dimension to this. Making an item look like it belongs is one side of the coin – making its under-the-hood attributes play nice with all of your game’s systems is the other.

This really is the height of the craft, as I see it. Including art & animation teams, designers, and back-end blockchain boffins makes this an all-hands-on-deck situation, however brief, to make item reimagination work.

Think of the amount of effort that goes into bringing Bayonetta into Smash, with all of its playtesters and balance experts, all its artists, all the liaising with the IP owner, just to make sure the game is faithful to Bayonetta while also fitting that cog into Smash’s fighting systems.

It’s an extraordinary task, and one the game’s development and marketing was planned around. When we talk about full-throttle asset reimagining, we’re talking about this level of commitment.

Thankfully I think metrics from a game’s dynamics will act as a guide. Perhaps your vanilla FPS doesn’t use the same attributes for weapons as the steampunk RPG you’re importing from. What would the hip accuracy of steampunk guns be? How much damage would gas-powered weapons do in a world of Kevlar? One steampunk weapon happens to have a poison effect, how does that translate over?

Hard problems to solve. But measures like TTK (Time to Kill) will point the way for designers, allowing them to work backwards from these metrics and fill in the missing pieces. If we know high, mid, and low skill players have TTK ratings of X, Y, and Z with a particular weapon, those are valuable benchmarks to hit while tweaking the reimagined weapon's attributes.

The art and systems-level problems are nothing to sneeze at, but there’s also another element I’ve put at this end of the spectrum: Story.

Items are easy to focus on because we can visualize them, but cross-game entities are just as likely to be quests, dialogues, histories, achievements, and more.

Meaningful story paths for prior decisions are no longer bound by the limits of a single game (or series). That opens up enormous possibilities – and enormous headaches for the narrative designers.

Likely, this will start out as Easter eggs, optional quest dialogue, small rewards for past deeds, and whatever the story equivalent of “low effort” is. Just like the leftmost end of the scale – check the wallet, see the thing, casually acknowledge it in the game and move on.

But eventually people will take this to the next level. Cross-game quests are almost like a new genre unto themselves, and while some gamers are cold towards NFT tech now, this is something too tasty for narrative designers to pass on forever.

Like I mentioned in this piece about cross-game items, for those who truly open up their IP for this, it serves as a kind of open-source fiction.

Aspiring storytellers will add to the decentralized heap of content. Curation and aggregation become services of their own. The quality will rise to the top, and become casually known as canon. Other tales will be forgotten. Being referenced and built upon will be a badge of honor, similar to citations in academia.

Thankfully, each developer has infinite options for just how much they want to incorporate this kind of storytelling. It’s up to them how much they want to commit to new content solely triggered by cross-game data.

There’s perhaps a whole section of the above chart that’s missing.

Many indie developers are excited about building towards cross-game items (we work with several), but you don’t even need to be a developer to contribute. There’s a whole category of contributors outside the game dev space, and they’ll play a substantial role in what’s to come.

I’m not talking about in-game user-generated content, the likes of which you see in Roblox. I’m talking about people taking it upon themselves to add to an ecosystem of content, without even knowing which games will be made with it yet.

They’re getting started before the game developers even begin.

Take the Loot project for example, which has a community contributing lore, images, and other functionality. All to be included in future games, all adding to the value of these digital assets.

There are games being built around this, but there will also be completely separate projects that choose to use elements of it in a plug & play manner, simultaneously strengthening and onboarding their community.

Some of these will be games from crypto natives focusing on play-to-earn, and some of these will be from career game designers who understand the art and science of joyful fun and intrinsic reward.

Veteran game designers have the advantage here - it’s harder to make a game than it is to make an NFT - but no matter their origin, teams who put in the labor to recognize external assets will reap the benefits of getting established communities to skip multiple layers of the marketing funnel. In many cases, that effort is likely to be more effective than advertising dollars.

Importing iconic weapons from here, acknowledge achievements from there, take a memorable NPC from here, build a door opened by a special key from there. If only a small percentage of each playerbase checks out how you’ve integrated their prior adventures, that can still be a great time investment on your part.

Far more than anything coming out of Zuckerberg’s brain, this will be the metaverse of gaming. Built by gamers and devs just wanting to make something cool in an open, integrated way.